http://islamicommentary.org/2014/09/freedom-of-expression-for-some-by-haiyun-ma-and-i-wei-jennifer-chang/

Chinese Academic Given Life in Prison for Uyghur Website; Radical Han Separatist and Nationalist Web Site Flourishes

by HAIYUN MA and JENNIFER I-WEI CHANG for ISLAMiCommentary:

The sentencing of a Uyghur economics professor, Ilham Tohti, on September 23 shocked many people including human rights groups and scholars of Xinjiang studies. Mr. Tohti, a critic of China’s policies in Xinjiang, and an advocate of Uyghur-Han dialogue, has been found guilty of separatism.

While not entirely unexpected, it came as a shock that a Beijing-based professor could be convicted primarily because of his management of a web forum, Uighurbiz.net — a site that in fact, far from advocated separatism, but encouraged dialogue.

With a focus on China’s Xinjiang policies and on Uyghur culture, history, economics, and other areas of inquiry, Uighurbiz included Tohti’s opinions, commentaries, and translated or re-posted articles about Uyghurs or other minority nationalities in China. Uighurbiz.net was widely regarded as a bridge for connecting the Uyghurs and the (ethnically Chinese) Han, for promoting mutual understanding between them, and for seeking better policies in Xinjiang.

It should also be highlighted that what Mr. Tohti did was completely within the bounds of China’s Constitution and other legal frameworks.

Human Rights Watch China director Sophie Richardson wrote in an op-ed, “Tohti has consistently, courageously, and unambiguously advocated peacefully for greater understanding and dialogue between various communities, and with the state. If this is Beijing’s definition of ‘separatist’ activities, it’s hard to see tensions in Xinjiang and between the communities decreasing.”

While the web site had been transferred from a domestic to an overseas server at one point, it is no longer functioning. The last posts on the site, nearly a year ago (10/10/2013) were a short piece by Tohti offering congratulations on the Muslim festival of Eid Kurban, and an article stating that one of his students was arrested and forced to lie about Professor Tohti. (It’s not clear whether Tohti himself had taken the website offline or whether it was shut down by the government. Using the Wayback Machine, it’s archived here: http://web.archive.org/web/20131019093409/http://www.uighurbiz.net/)

It’s also important to point out that both the separatism charge and the punishment Tohti received – life in prison — is much more severe than what the majority of Han political dissidents have received. It’s a heavy-handed response.

As Maya Wang, a researcher from Human Rights Watch, told The New York Times, she could not recall any Han Chinese advocates or dissidents receiving a life sentence in recent years.

This is confirmed by leading academics on Xinjiang. Georgetown University Prof. James Millward mentioned in his timely op-ed in The New York Times that the sentence was longer than those given to other Chinese dissidents.

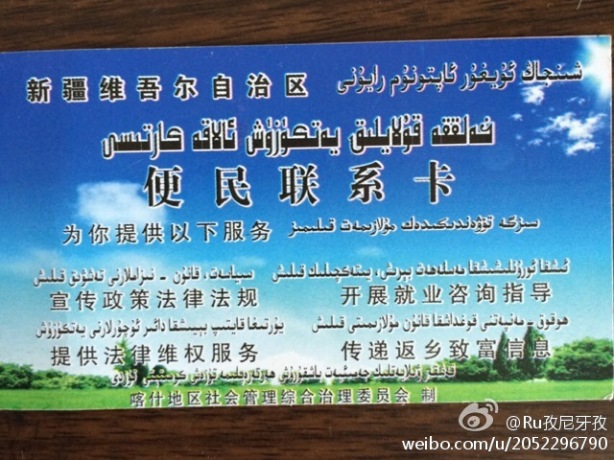

Tohti’s conviction in particular — that of a Uyghur scholar for a personal Beijing-based web forum he managed — indicates a shift in the (Chinese-run) Xinjiang government’s suppression pattern. It appears to be a new tactic for cracking down on Uyghur dissidents: going after their websites and accusing and in some cases convicting them, mostly falsely, of separatist activities.

Why the shift in framing and tactics?

The Xinjiang government had long attributed the source of violent protest in Xinjiang to Afghanistan, Syria, Chechnya, Pakistan, or other Muslim majority regions or countries, but so far not a single Uyghur attacker accused of recent attacks in Beijing, Kunming, Urumqi, Shache, and other places, has been found to have such alleged international connections.

So it’s not surprising that following the 9/11 terror attacks in the United States, the Chinese and Xinjiang governments started blaming a homegrown terrorist group — the Turkistan Islamic Party (formerly the East Turkistan Islamic Movement, ETIM) — for igniting unrest in Xinjiang.

Interestingly, the very existence of ETIM (and later TIP) is in question. The U.S removed ETIM from it’s terrorist organization watch list. This made China’s accusations that ETIM was the source of Xinjiang unrest difficult. In recent years, China shifted from blaming ETIM as an organization to claiming ETIM/TIP audio-video propaganda was motivating the unrest.

To say that Uyghurs were incited to violent attacks based on this propaganda, is a weak connection at best. Without considering that the government’s exclusionary policies toward Uyghurs might be at least partially to blame (extensively detailed in ISLAMiCommentary and by many Western journalists), the Xinjiang government now seems focused on cracking down on so-called “separatist” Uyghur web forums that they see as advocating separatism, terrorism, and extremism.

The Xinjiang government went to Beijing and arrested Mr. Tohti in order to prove that there is a “mastermind” or “ideologue” behind the unrest in Xinjiang. The government even went so far as to accuse Mr. Tohti and his website contributors of the July 5th riot in Urumqi in 2009 that caused the death of hundreds of people. (The Xinjiang government had previously accused the World Uyghur Congress and its leader Rebiya Kadeer as being behind the July 5th riot. Perhaps that didn’t stick.)

While Mr. Tohti was sentenced primarily for his running of a reasonably moderate, though critical, web forum on the Uyghurs and Xinjiang, many prolific Han ultra-nationalist websites have openly advocated Han racism, Han chauvinism, Han militarism, and even Han separatism by spreading hate speech against non-Han peoples.

The site http://www.huanghanzu.com (literally, “Heavenly Han” people) presents the most radical cultural attacks and portrayals of non-Han peoples, including foreigners such as Jews, people of color, and Chinese minorities such as the Uyghurs and the Hui Muslims.

While Prof. Tohti has called for dialogue and cooperation between the Uyghurs and the Han, http://www.huanghanzu.com publicly discusses the extermination of “evil Jews” who have dominated the World (including in Hong Kong), elimination of “dirty Negros” in Guangzhou, the expulsion of Muslims from China, and the “cleansing” of Han traitors and Han women who have “dirtied” themselves by being easily accessible to foreigners, and the like.

The forum manager is “Da Han Wu Di” (literally, “Great Han without matching enemy” or simply “undefeatable Great Han”), and most articles or comments on this web site have supported hate crimes, racism, or anti-Semitism.

Compared to Mr. Tohti’s Uighurbiz.net, Huanghanzu.com not only supports racism, but also advocates Han separatism by spreading hatred against non-Han peoples. If Mr. Tohti is being punished primarily for his Uighurbiz site, why doesn’t the “Undefeatable Han” get jailed for his “Heavenly Han” website ?

One could argue that Beijing is not censoring that site because it believes in freedom of expression. But, as is evident in the case of Tohti and Uighurbiz.net, the government doesn’t advocate freedom of expression for all.

It is China’s suppression of Uighurbiz and it’s punishment of the site’s manager, together with it’s refusal to censor the Huanghan forum, that reflects a dangerous social and cultural tendency. Punishing non-Han intellectuals for their expression of dissatisfaction only enlivens Han nationalism and bolsters Han separatism and racism, which is not a good sign for China’s minority populations and the government’s stated commitment to their rights under China’s Constitution and Ethnic Regional Autonomous Law.

Haiyun Ma teaches in the history department at Frostburg State University in Maryland. His teaching and research interests are Chinese History, Islam and Muslims of China (including Xinjiang), China-Middle East relations, and China-Central Asian Relations. He is an expert on China-Middle East relations at the Middle East Institute, and a regular contributor to ISLAMiCommentary.

I-wei Jennifer Chang is a D.C.-based writer and researcher on China, with an MA in international relations from the University of Maryland. Her research interests include Sino-Gulf relations, U.S.-China relations, Chinese foreign and security policies, China’s oil security, ethnic conflict, and U.S. foreign policy. She has conducted fieldwork in Beijing and Shanghai, interviewing numerous Chinese scholars, think-tank researchers, and former ambassadors.